I have accepted that I must simply work at improving my reading knowledge of German. This shouldn't be impossible since I once studied German and spent one summer with a family near Tübingen. However, no polished German translations are about to turn up here under my authourship.

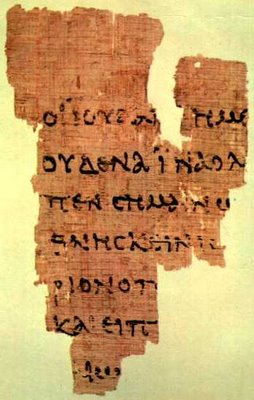

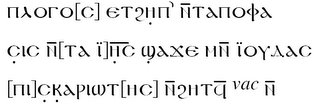

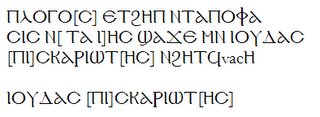

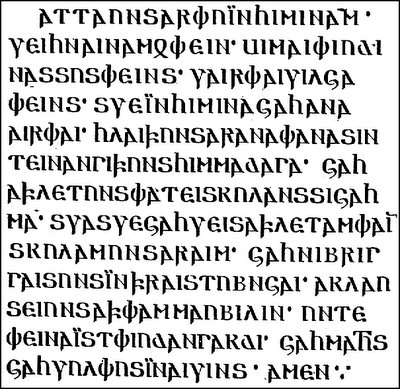

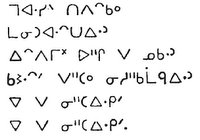

This is the first 20 words of Psalm 12:6-7 * in

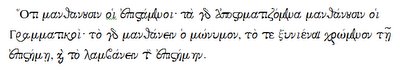

Tironian notes. The best resource that I have found so far on Tironian notes is Boge's Griechische Tachygraphie and

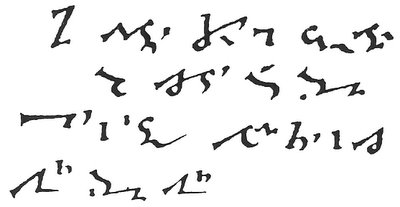

this site with images of a manuscript by

Karl Eberhard Henke. This will keep me busy for a while.

Tironian Notes are attributed to Tiro, who worked for Cicero.

The National Court Reporters Assocation has a great article on

The History of Shorthand By Anita Kreitzman. Here is the section on Roman shorthand.

"Shorthand in ancient Rome seems to have appeared as early as 200 B.C. with the poet Quintas Ennius, who devised a system of 1,100 signs. But it was not until Plutarch in 63 B.C. that definite and indisputable evidence of the use of shorthand is recorded. He writes of the debate on the Catilinian conspiracy that was recorded in shorthand in the Roman Senate as the famous orator Cicero expounded his views.

It is interesting that Cicero was indirectly responsible for the method of shorthand devised by Tiro. Tiro was a slave of Rome and had been granted his freedom by Marcus Tullius Cicero. Upon becoming a freedman he adopted the first two names of his master and thereafter was known as Marcus Tullius Tiro. Highly educated, "he then became Cicero's secretary and confidant," and as such had the opportunity and fortunately the intelligence and skill to invent a system of shorthand that was to be used in the Roman Senate and as a basis for future shorthand systems. Initially, his system involved abbreviations of the more popular words with the remainder of the text filled in from memory using context clues. Not a very accurate method, but Tiro continued to improve on his system by devising further abbreviations for common sentences and phrases used by the orators of the day. He is also credited with inventing the ampersand, which is still in use today.

In the Curia, as many as 40 shorthand writers were stationed in the different areas. They recorded what they could and their transcripts were then compared and compiled in order to record the complete orations of such greats as Cicero and Julius Caesar. Today, in our own Congress, a similar system is used except that the reporters work in relays.

Famous writers such as Horace, Livy, Ovid, Martial, Pliny, Facitus and Suetonius make mention of shorthand in ancient Rome. Julius Caesar, himself, was proficient in shorthand. And to be proficient in shorthand was not an easy task.

The ancient Roman scribe did not have paper, pen, pencil or ink. How, then, did they record the events? The medium was a tablet with raised edges covered with a wax layer. As many as 20 such tablets could be fastened together to form a book. A stylus, similar to a pencil, was used for the actual writing. The point was ivory or steel, the other end flat in order to easily smooth the wax when the notes were no longer needed and a new tablet required. Ironically, it was with such instruments that Caesar was stabbed to death. Had Caesar the foresight to see his fate, perhaps he would not have pursued his interest in shorthand.

Others who demonstrated an avid interest in shorthand writing included Titus Vespasian Caesar, who was so skilled at shorthand that he participated in "contests for wagers and personally taught the art to his stepson," and Augustus Octavianus, an expert shorthand writer who "appointed three classes of stenographers for the imperial government." He considered the skill so important that he taught it to his grandchildren. And even Seneca, the great orator and philosopher, who became so fascinated with shorthand that he improved Tiro's system by adding several thousand abbreviations of his own."

Somehow I could not abreviate this article and extract the interesting parts - it is all too fascinating. I am off to study Karl Eberhard Henke.

Notes:

Image is from "Du Charactère Sténographique de Toute Écriture." Yves Duhoux. Studia Minora Facultatis Philosophicae Universitatis Brunensis N 6-7, 2001-2002. Unfortunately Duhoux does not give the location for the Latin manuscript but it was also mentioned in M. Proux. 1910. Manuel de paléographie latine et française. Album. Paris.

Karl Eberhard Henke:Tironische Noten. MGH-Bibliothek Hs. B 16. Digitale Ed. [Manuskript ca. 1954] / Konzeption u. Bildbearbeitung: Arno Mentzel-Reuters

Boge, Hebert. Griechische Tachygraphie und Tironische Noten. 1973. Akademie Verlag. Berlin.

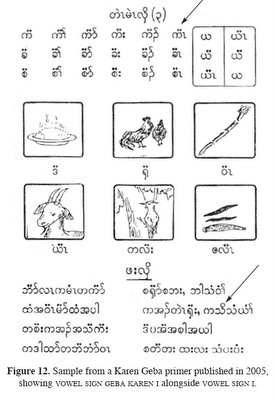

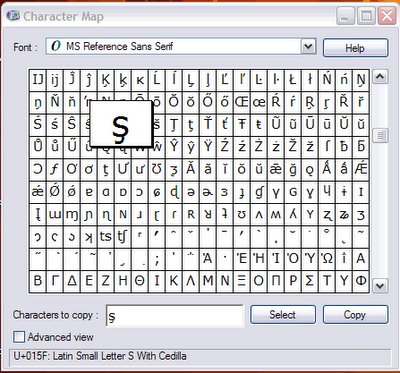

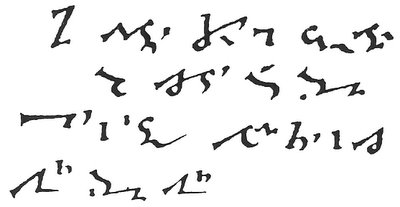

I was surfing the internet looking for more on the diæresis (note that I have used the more correct U+00E6 today) when I received notification of a proposal that included this dear little thing. Not a diæresis after all, it is the proposed character MYANMAR VOWEL SIGN GEBA KAREN I U+1097.

I was surfing the internet looking for more on the diæresis (note that I have used the more correct U+00E6 today) when I received notification of a proposal that included this dear little thing. Not a diæresis after all, it is the proposed character MYANMAR VOWEL SIGN GEBA KAREN I U+1097. The usual MYANMAR VOWEL SIGN I is U+102D. (I have just used Babelmap to confirm that I am reading this correctly.)

The usual MYANMAR VOWEL SIGN I is U+102D. (I have just used Babelmap to confirm that I am reading this correctly.)